The topography, which humanity has constantly struggled with from history to the present, is now being destroyed by us the moment it becomes an obstacle to us. And now we are creating a new layer-topography with the structures we have built and the areas we have opened, as if laying a new cover on topography. At this point, today’s meaning of topography, which used to have a different meaning for us, should be discussed. One of the certain points I reached with the information I gathered as a result of the research was that Istanbul experienced a regional “reset” from time to time. Sometimes a flood, sometimes an earthquake or a fire allowed Istanbul to be rebuilt in order to catch up with time, and almost offered an excuse for transformation.

If there is a destruction that will cause transformation for Istanbul, how will the rebuilding of

the city be?

If there is a destruction that will cause transformation for Istanbul, how will the rebuilding of

the city be?

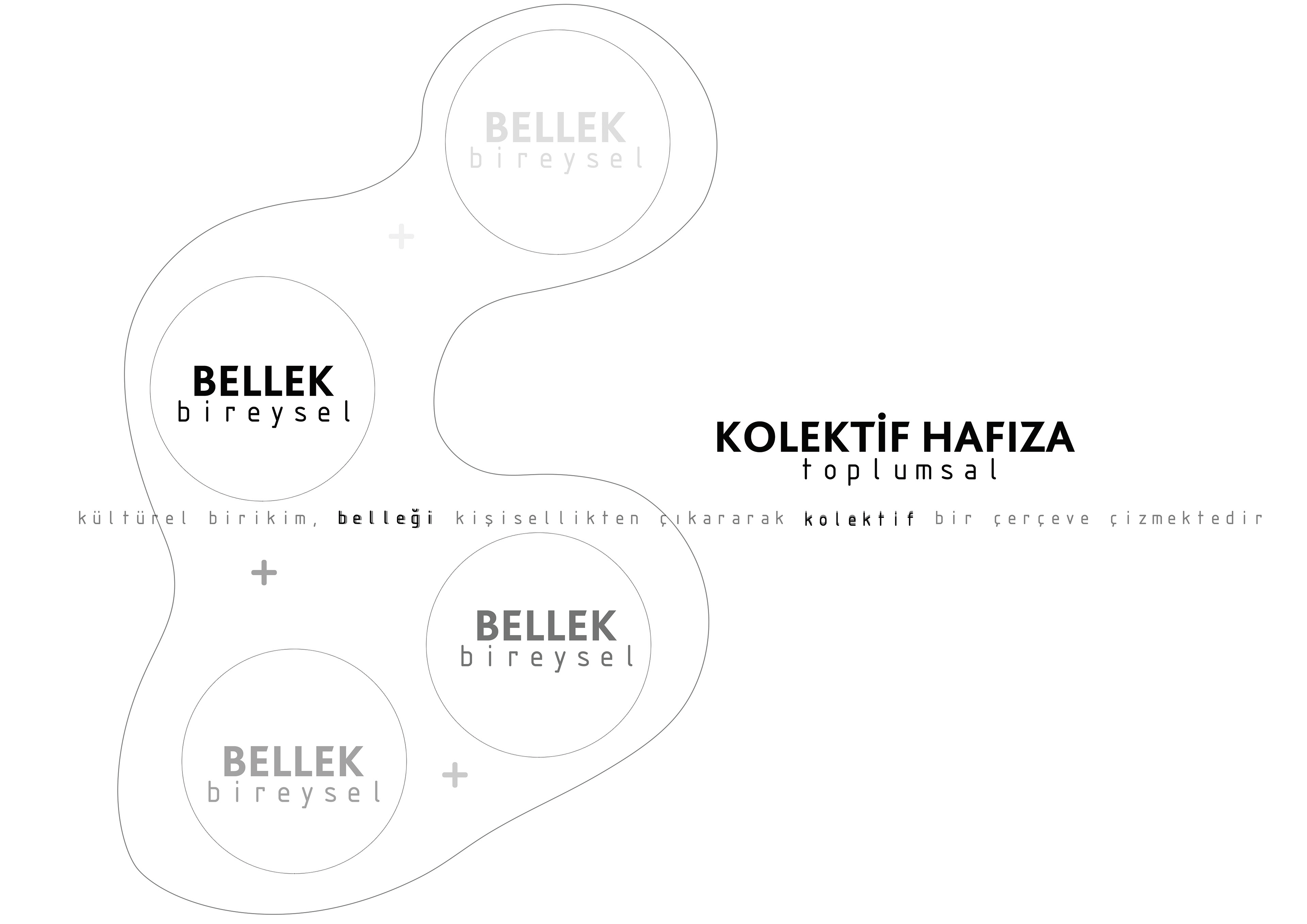

Silhouette and Urban Image

The most obvious effects of the phenomenon of globalization, which developed depending on the modernization process, have been on cities and their lives. Urban areas are places where civilization develops and social transformations take place. Silhouettes can be called as the view of the elements of the natural and built environment of cities from a distance, and silhouettes provide recognition and serve as identity. They provide representation with the images they reflect, but these images are not fixed and open to change. Their borders are not clearly defined, they can transform depending on time and space. The silhouette of Istanbul also serves as an identity for him and provides him with world recognition. It has been articulated, changed, transformed, destroyed, dispersed and rebuilt over the years, and has rebelled against time. At this point, silhouette and memory have entered our working area.

The most obvious effects of the phenomenon of globalization, which developed depending on the modernization process, have been on cities and their lives. Urban areas are places where civilization develops and social transformations take place. Silhouettes can be called as the view of the elements of the natural and built environment of cities from a distance, and silhouettes provide recognition and serve as identity. They provide representation with the images they reflect, but these images are not fixed and open to change. Their borders are not clearly defined, they can transform depending on time and space. The silhouette of Istanbul also serves as an identity for him and provides him with world recognition. It has been articulated, changed, transformed, destroyed, dispersed and rebuilt over the years, and has rebelled against time. At this point, silhouette and memory have entered our working area.

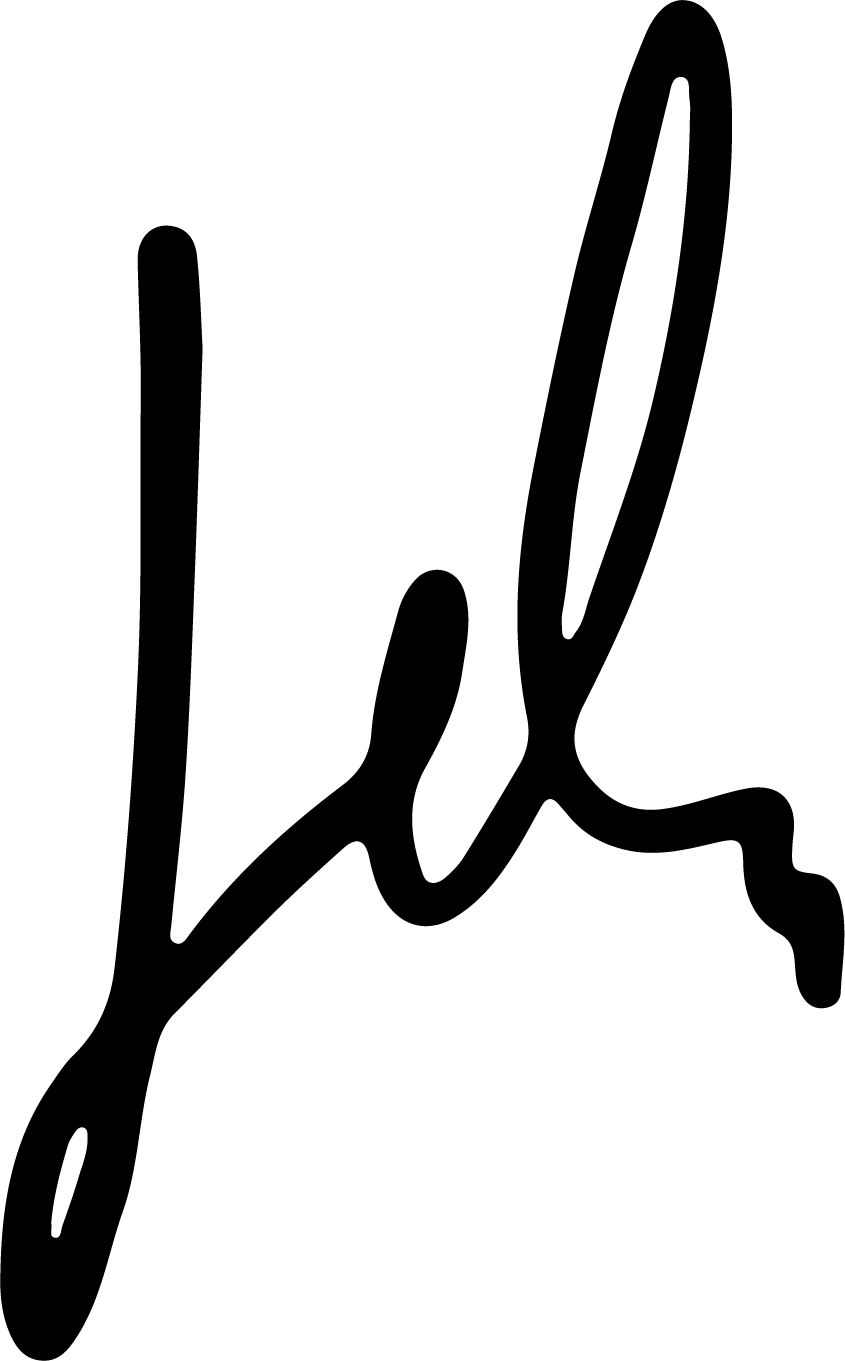

Image of the City and Collective Memory

Spaces take on the task of recalling and reminding us, and while doing these, they are fed from memory. Individual memory is formed when time, space and image come together in the mind of the individual and gain a reminder and descriptive function; Collective memory, on the other hand, is a reflection of the common elements that societies have built from the past to the present, and it is social and related to the place. Memories, people, values etc. accumulated in the collective memory constitute some reference points in the space. The sum of these values gives scale to the space and the value adopted by the society causes the emergence of common spaces. Memory simultaneously folds over the past, making room for the future moment. In this transformation, in order to become conscious of the moment stuck in the present, Marc Auge (1999) comments that the act of forgetting is a social necessity. While making an analogy between life and death with the relationship between forgetting and memory, Auge mentions that memory summons the moments from the past by reducing and transforming, and emphasizes that forgetting is inevitable like death. According to Italo Calvino, cities are places of exchange for those who live in them, but they are places where not only goods with commercial value are exchanged, but also where individual memories, stories, experiences, and the language used are exchanged. Urban spaces are places where citizens come together and create a common production as a result of these collaborations, where the traces of the memory of the space are kept alive.

Spaces take on the task of recalling and reminding us, and while doing these, they are fed from memory. Individual memory is formed when time, space and image come together in the mind of the individual and gain a reminder and descriptive function; Collective memory, on the other hand, is a reflection of the common elements that societies have built from the past to the present, and it is social and related to the place. Memories, people, values etc. accumulated in the collective memory constitute some reference points in the space. The sum of these values gives scale to the space and the value adopted by the society causes the emergence of common spaces. Memory simultaneously folds over the past, making room for the future moment. In this transformation, in order to become conscious of the moment stuck in the present, Marc Auge (1999) comments that the act of forgetting is a social necessity. While making an analogy between life and death with the relationship between forgetting and memory, Auge mentions that memory summons the moments from the past by reducing and transforming, and emphasizes that forgetting is inevitable like death. According to Italo Calvino, cities are places of exchange for those who live in them, but they are places where not only goods with commercial value are exchanged, but also where individual memories, stories, experiences, and the language used are exchanged. Urban spaces are places where citizens come together and create a common production as a result of these collaborations, where the traces of the memory of the space are kept alive.

Mortal Born Structures

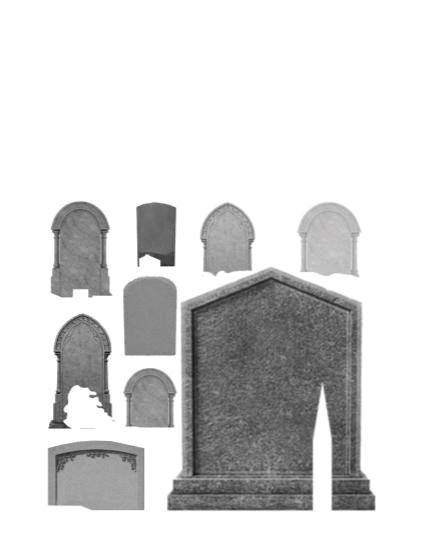

In order to preserve the collective memory, we need to respect and preserve values. So, is respect not destructive? Or is respect rebuilding? We know that human life is limited and time runs like an hourglass after birth. We know that we will die, that we will perish, but that we will live in the memories of the people who love us. Well, aren’t structures also mortal like humans? We know that they also have a birth and death and a place in memory. When we enter a place, we remember the people and events we spent time in that place. So, when we build tombs for our loved ones, why don’t we build for structures, on the contrary, we treat them as if they will live forever. For whom and for how long do we convey history.

In order to preserve the collective memory, we need to respect and preserve values. So, is respect not destructive? Or is respect rebuilding? We know that human life is limited and time runs like an hourglass after birth. We know that we will die, that we will perish, but that we will live in the memories of the people who love us. Well, aren’t structures also mortal like humans? We know that they also have a birth and death and a place in memory. When we enter a place, we remember the people and events we spent time in that place. So, when we build tombs for our loved ones, why don’t we build for structures, on the contrary, we treat them as if they will live forever. For whom and for how long do we convey history.

Future Transfer Alternatives

One of the ways we can follow when a building that has taken a place in memory is destroyed is to get it back on its feet. When this re-enactment is not done with qualified design and protection, instead of glorifying the spatial memory, it destroys the memory. If a structure that has shaped the surrounding context over the years is destroyed, we need to reconsider that context because the biggest factor in the equation comes out of the multipliers. While this creates potentials for rebuilding, the void poses a great threat to the life and memory around it. To eliminate this threat, we make restorations to preserve history, preserve our culture, and pass on our traditions to the next generation.

When there is no structure that was completely destroyed in the earthquake and that we can protect, restore and revitalize, we can provide the reconstruction of that structure with today’s technology, but even though the structure we built looks like it was in the past, it cannot have a historical value because it was built in today’s conditions, it is only a reflection and revival of history. In such a case, can we question this context again and think of building cemeteries that will remind us of historical buildings and environments without building them?

One of the ways we can follow when a building that has taken a place in memory is destroyed is to get it back on its feet. When this re-enactment is not done with qualified design and protection, instead of glorifying the spatial memory, it destroys the memory. If a structure that has shaped the surrounding context over the years is destroyed, we need to reconsider that context because the biggest factor in the equation comes out of the multipliers. While this creates potentials for rebuilding, the void poses a great threat to the life and memory around it. To eliminate this threat, we make restorations to preserve history, preserve our culture, and pass on our traditions to the next generation.

When there is no structure that was completely destroyed in the earthquake and that we can protect, restore and revitalize, we can provide the reconstruction of that structure with today’s technology, but even though the structure we built looks like it was in the past, it cannot have a historical value because it was built in today’s conditions, it is only a reflection and revival of history. In such a case, can we question this context again and think of building cemeteries that will remind us of historical buildings and environments without building them?

Brief history of the Cemetery

Why did cemeteries arise? 120,000 years ago, humans began burying and building commemorative hills to honor the deaths of loved ones. Later, the cemetery was used for centuries as an urban garden function, where people spent their daily lives, celebrated festivals and grazed animals, apart from being places where people buried their loved ones and only visited at certain times. Towards our recent history, cemeteries lost these features. Cemetery culture connects us with our past history. We remember and we remember, we are happy or we lament. It has a place in our memory, both good and bad. How do we do that if we build cemeteries for their structures?

Why did cemeteries arise? 120,000 years ago, humans began burying and building commemorative hills to honor the deaths of loved ones. Later, the cemetery was used for centuries as an urban garden function, where people spent their daily lives, celebrated festivals and grazed animals, apart from being places where people buried their loved ones and only visited at certain times. Towards our recent history, cemeteries lost these features. Cemetery culture connects us with our past history. We remember and we remember, we are happy or we lament. It has a place in our memory, both good and bad. How do we do that if we build cemeteries for their structures?